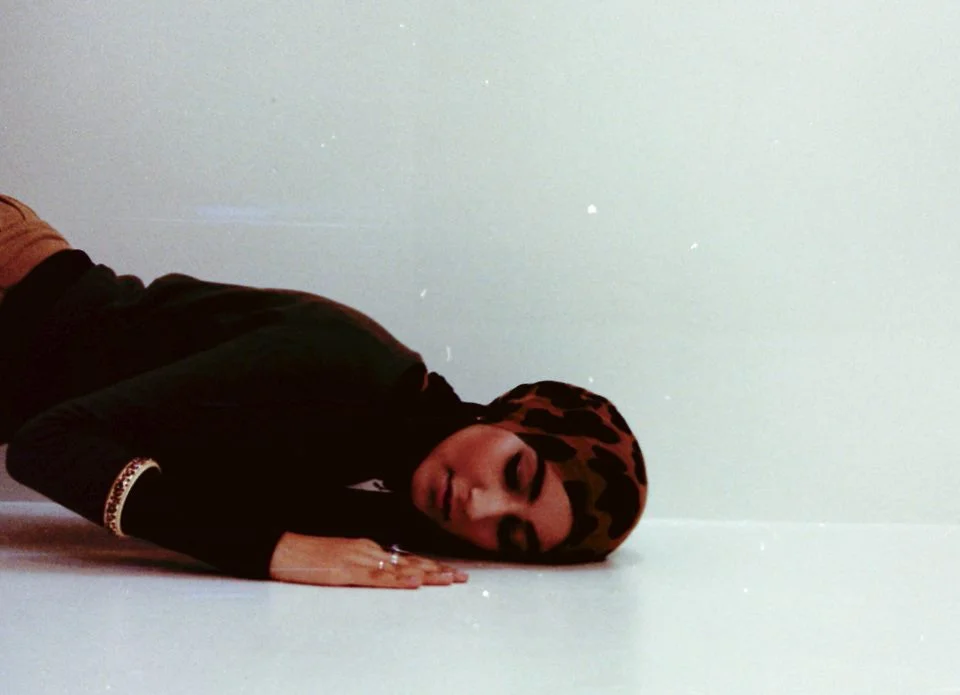

Photo by Zayn Thiam

“It’s not what you said, but how you said it.” The age old rebuttal seems to come up over and over again during uncomfortable conversations with loved ones.

This is the tricky thing about communication. We can have the tools but not put them in the right configuration. We can have all of the intentions to carefully cradle our friends’ hearts like a newborn baby while we listen to exactly what made the day defeating. We intend to empathize. We put energy behind sympathizing. We make time and give effort. Yet, at times, things can still fall flat. Hell, trying to offer help can even make things worse. There’s no magic recipe for the perfectly tailored supportive communication as we try to care for one another.

When mental illness is involved, it inherently complicates things. A temporary bout or episode of depression or anxiety differs greatly from being medically diagnosed as neuroatypical. It is healthy, normal, reasonable and expected for various profound transitions in our lives to become triggering events. However, when these episodes are specifically tied to the ebbs and flows of a mental health diagnosis, it becomes even trickier to understand how to be appropriately supportive.

Support is Never Perfect

I’ve felt this on both sides of interactions. I want my friend who is having a bad day to feel better. I also know, from their own disclosure, that today is the “especially bad” part of a cycle between euphoria and sadness. The cycle is the norm for their depression diagnosis. The cycle is ever-present, even with the support of medicine and weekly therapy. Actually, the combination of both keep the low tide feelings from hitting rock bottom and the high tide feelings from enticing them to physically test their body’s limits by attempting to “fly” between two rooftops like a parkour stuntman.

First, when we look to support our friends, it most often is in the form of encouragement. Our friends feel disturbed, tired, anxious or distraught. So, of course, the logic of our heart follows that being in their corner means to fight on their behalf. Fighting the bad feelings with good feelings truly seems like the right thing to do. At times that is a crucial part of the puzzle. In the best cases, though, we waltz right past the point where we “meet our friends” where they are and hold space for their full reality.

We hold space for them by acknowledging the legitimacy of what is happening. We hold space for them by acknowledging that they may not be able to fully explain the details of their specific triggers. The message they have delivered is that they need us present (in whatever form that takes). The message we can return is that we are committed to help them create a sense of safety in what often may be a deeply frightening encounter – regardless of how much a “norm” it may be for their manifestation of their disorder(s).

Next, we can avoid language that minimizes the intensity and the legitimacy of their experiences, such as “I know you’re smarter than this.” The kissing cousin of “I know you’re stronger than this,” this appeal to simply tap into intellect during challenging episodes has time and again been one of the most subtly delivered defeating responses. When we see our friends in the midst of a “dark” episode, their vulnerability allows us to see them in a weakened state. Which is exactly why phrases like "you're strong" can be unintentionally harmful.

I’ve even been guilty of saying these phrases myself with the best of intentions. Reflecting on our motivations to respond that way to those we are trying to support can be helpful in proactively creating intentional, loving, and healing spaces in our close relationships with folks living with chronic mental illness or behavioral disorders.

We must acknowledge that we rely on our conscious minds, imprecise as they may be, to manage the symptoms of mental illness because reaching into the subconscious for guidance is still beyond our collective control. It is impossible to out-think, to out-smart or to out-wit something that is part and parcel of how our brains are wired. When we, or those we care about, have a mental health diagnosis the concept of normal stops being so easy to universalize and becomes a highly personalized concept.

Intelligence Can't Stop a Panic Attack

I remember how I poured time, effort and enjoyment into preparing my analysis for an essay based literature final. My inner nerd was excited to have fully familiarized myself with multiple manners of attack so that I could create a complex and compelling lens for analysis. Also, I offered an intersectional framework because the author wasn’t thinking about queer people like he should have been, and that’s why this would be THE synthesis that bumped my final grade up from a B to a strong A.

What no one could warn me of was how the test would actually play out. No one could warn me that somewhere between the start of the test and looking for a better pen, the inherent stress of being in a testing environment would trigger a panic attack.

The panic attack was considered “discreet” because there wasn’t any writhing on the floor. No one rushed over to check my pulse because I was starting to slump in my seat. No one attempted to relieve my airway because I was starting to turn blue. No, I merely had the acute displeasure of a frightening onslaught of thoughts going at 90 miles an hour, which turned into ten minutes less time than expected to finish the final. It turned into scraping around for the simplest thesis I could make materialize on a page and a creative stitching together of whatever items from the text that my memory could access at the moment.

Oh, also my panic attack turned into an agonizing final two minutes of wide-eyed, frantic proofreading. It materialized into me holding onto that B and feeling relieved that I had rallied because the exam could have shifted the tide further to leave me with an overall C grade in the course. Yes, all of my intelligence was present. All of my preparation was present. All of my desire and discipline to excel was present. Accessing this, though, was complicated by something outside of my control in the moment.

In the aftermath of the storm, I also remember the words of a friend. “But you did it,” they said. “You showed up. You hustled, and you gave what you had to give. I’m proud of you.” As each sentence hit my ears, the parameters of genuine support appeared. In the moment, I felt seen and heard. The haze of that which I was unable to actively control no longer seemed as powerful. Hindsight has taught me to appreciate the full gravity of the interaction. My friend held space for me in a supportive way. At no point did my experience become reduced to a handful of symptoms, outcomes and results. At no point was my personhood or intelligence dismantled in an attempt to rationalize what happened. My friend modeled for me what we can model for each other. Acknowledge the effort. Praise the hustle. Remind one another to see our inherent value.

* * *

As we learn to support each other and ourselves, we can always seek to improve our understanding of what that support best looks like. We can acknowledge that our personal norms differ substantially from those of others. This is especially true when a mental health diagnosis is present. We can hold space for each other without judgment and pretense.

We can hold space in so many ways. Chief among them is not conflating the idea that intelligence provides an absolute advantage in managing a mental health diagnosis (whether they are in formal treatment or not). Yes, you are smart. Yes, your friend is smart. Yes, your loved one is smart. And yet, the act of using our emotional intelligence rather than logic in supporting each other is truly one of the smartest ways we can respond to life’s challenges.

Edited by Dominic Bradley & Dom Chatterjee

We need community support to continue publishing!

Articles and artwork like these are only possible through your contributions. Please donate today to sustain the wellbeing of artists, writers, healers, and LGBTQ2IA+ people of color.

You can also support our team by picking up

a Rest for Resistance print zine.

Image description:

A photo in black and white. A Black person with short hair is looking down, the left side of their face turned away. They have a septum piercing. The background is a white wall, their shadow lightly cat against it.

About Zayn Thiam:

Zayn Thiam is an African queer artist living in D.C. after 27 years of hopping around the globe. Photography, writing, painting and henna tattooing are a few of their loves. They are also an energetic healer and loves to read the tarot for themself and others. See their artwork at @negrotesque and @twocameracats on Instagram.

About Joel N Jenkins:

Joel N Jenkins is a writer, editor, and native of Queens, NY currently working hard to acclimate to the California sunshine. As a McNair Scholar at the University of California, Davis, his research focuses on Black queer men’s cultural contributions to our understanding of American English. When he’s not studying, you can find him at @joelscribes on Twitter.