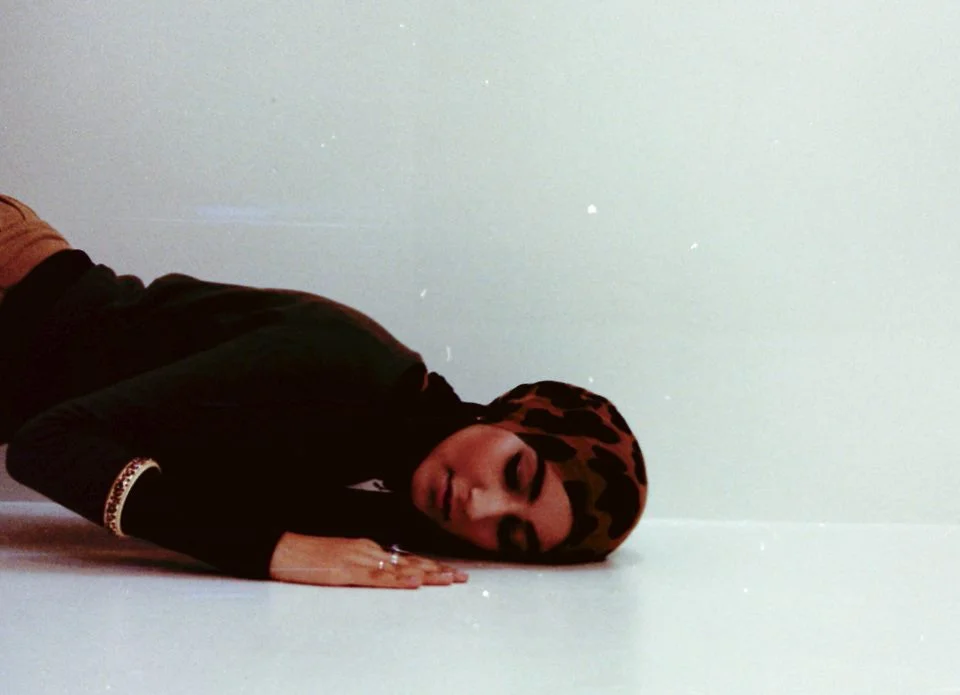

Photo by Soraya Jean-Louis McElroy

I am often asked why I chose to enter the field of mental health, and I was repeatedly asked when I interviewed for graduate school. I always reply with some variation of, “I saw the stigma surrounding mental health in my community and knew I needed to help change it,” or “I believe that mental health is the foundation of all liberation work and that we cannot move forward without achieving mental wellness,” or “I saw how many queer and trans people of colour struggle with mental illness and wanted to help.” All of these statements are true; but they are not the reason I originally became interested in psychology.

The real reason is hidden, buried deep, a skeleton in a closet which I rarely discuss.

I was later to realize that it was all about control.

* * *

It all began at the age of 13. I never eased into it; it was never a diet gone too far. I remember waking up one morning and thinking to myself, “I don’t think I’ll eat today.” Later, doctors wouldn’t believe me. At the time, I went through my days restricting food here and there, eventually refusing to eat entire meals. It felt like a high, like I was flying through life. My previous melancholy dissipated; I had finally found an outlet. I was later to realize that it was all about control.

I baffled my parents. Both immigrants with humble roots, they couldn’t understand the concept of not eating when you had food sitting right in front of you. My father had grown up with a persistently growling belly, was underweight not because of a lack of desire but because of a lack of food. This only contributed to my increasing shame. I continued to shrink, smaller and smaller, in both body and mind.

Eventually, the high went away. It became robotic, just a routine to fill my days. The melancholy came back. I contemplated slitting my wrists just to get it over and done with, since I was killing myself anyway, only slower. I ended up swallowing half a bottle of Tylenol, having read somewhere in the dark recesses of the Internet that it would do the trick. I went downstairs, head slightly spinning, and made myself a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. I slathered the peanut butter on thick, knowing that none of this would matter tomorrow since I would be dead. Needless to say, my attempt at escape didn’t work. “Just another failure to add onto the pile,” I thought.

My mother was sick, had been sick all my life. Later, psychologists would tell me that I was probably envious of the attention she got, so I stopped eating to shift the attention to myself. This only contributed to my subsequent shame. On a routine hospital visit for her, she suddenly asked the doctor about me, why I wouldn’t eat. I was shocked.

The doctor weighed me. Obscene. Asked about my eating habits, to which I responded honestly. At this point, it was too late anyway. Plus, a part of me was crying out for help.

“Your daughter has anorexia nervosa,” the doctor said.

“What’s that?” my mother responded.

Luckily, we lived in Canada, where rehab means you stay there until you get better, not until your insurance runs out. Or that’s how it was back then, anyway.

I ended up at a hospital in a smaller town, far from where we lived. I was surrounded by whiteness the entire time, with the exception of a half-Indian girl who left soon into my stay. Still, she gave me some hope. I was to learn that eating disorders were a “white thing.”

When I began restricting, I didn’t know the name for what I was doing. I had simply found a way to control the life I felt was spinning away from me. Later, I believed that it was my burgeoning queerness and the rejection of my parent’s religion that led to this feeling.

The counselors at the clinic could not understand me. Kept pushing to figure out why I stopped eating in the first place. “You must have implicitly wanted to be skinny,” they reasoned. “No dieting at all before all of this started?” I was stubborn, unyielding; I told the truth. Of course, I had internalized white beauty ideals like we all had. But I had grown up in a brown neighbourhood, with brown kids, and I can’t remember ever worrying about my weight before that morning.

I still remember an exercise in which we were supposed to draw our ideal body shape. After a few minutes, we all held up our drawings. Everyone had drawn a stick-thin, boyish figure, with the exception of me. I held up a drawing of a curvy woman, large breasts and hips with a thin waist. They all stared and, again, did not understand.

It took the strength to love myself, deeply, before I could see what I was doing to my body as harmful.

Later, I was to relapse three more times, ending up in an inpatient unit for the most severe one. Several suicide attempts were to follow. There are more stories to tell. I still wonder whether having just one therapist of colour would have made a difference, would have provided me with some assurance that I was not alone.

None of my friends ever understood why I wouldn’t eat. After a particularly damaging summer in my undergraduate years, my classmates of colour queried, “Are you sick? What’s wrong?” They wondered if I had some terminal illness, or cancer. My white classmates looked at me with a knowing glint in their eye, some with envy. They knew, but no one close to me did. The white girls in my inpatient unit knew what I was going through but simultaneously had no idea. It was a terribly lonely existence. I didn’t feel comfortable with anyone.

I still struggle to tell people. My eating disorder is largely in my past, though I have to monitor myself when I get stressed. I rarely discuss those days, even with my closest friends. The overwhelming sense of shame at being a queer person of colour with an eating disorder still abounds. Anorexia is still considered a mental illness of the privileged, that afflicts only middle- to upper-class white women.

In the end, I largely healed myself. I used the coping skills taught to me in eating disorder units but those hospitals never cured me. I struggled for years to understand myself before I reached a place of relative calm. It took the strength to love myself, deeply, before I could see what I was doing to my body as harmful. It took leaving the toxic whiteness of my undergraduate institution and surrounding myself with people who love me and look like me. But even these people often do not understand what I have buried deep within.

It is time for me to step into the light, alongside the other people of colour, queer and trans folks, and marginalized people who have struggled with disordered eating. Seeing eating disorders as “white diseases” causes us all to feel immense shame in addition to the negativity we are already carrying in our bodies. While the stigma around mental illness in communities of colour has slowly decreased over time, there continues to be little to no understanding surrounding the root causes of eating disorders.

I hope increasing awareness that anyone can suffer from an eating disorder – regardless of race, class, gender identity, or sexuality – as well as creating community spaces where folks can process through their disordered eating and heal will help break down some of this shame and stigma. We still have a long way to go, but I am glad we are heading in the right direction.

We need community support to continue publishing!

Articles and artwork like these are only possible through your contributions. Please donate today to sustain the wellbeing of artists, writers, healers, and LGBTQ2IA+ people of color.

You can also support our team by picking up

a Rest for Resistance print zine.

Image description:

An abstract painting is mostly red with swaths of pink, yellow, and light blue. There are rough lines in white, some running vertical, others curving to form the shapes of faces featuring big eyes and big lips. The painting appears textured rather than flat.

About Soraya Jean-Louis McElroy:

Soraya Jean-Louis McElroy is a Haitian born, Harlem and Brooklyn raised mixed media queer womynist artist currently living and loving in New Orleans. Her love of black womyn and families, motherhood, nature, Afrofuturism, comics/graphic novels, and the African Diaspora are central themes in her work. Soraya is the co-founder of Wildseeds: New Orleans Octavia Butler Emergent Strategy Collective. Wildseeds work, steeped in Black feminist traditions of survival and healing, engages Octavia Butler and other speculative/sci-fi and fantastical authors a resource for social change. Soraya is constantly imagining and creating new work and was awarded the Alternate Roots Visual Scholars grant in 2014. Most recently Soraya was co-organizer of Black Futures Fest: A Celebration of the Black Fantastic in New Orleans 2015.

About Samia Lalani:

Samia Lalani is a genderqueer mental health advocate and counseling psychology student currently residing in DC. Born and raised in Toronto, they have also lived in Atlanta and New Orleans. They are of mixed Arab, African, and South Asian descent. Their goals and endeavours include conducting community-based research on, with, and for QTPOC; fostering safe space for QTPOC in academia; and advocating for mental health as a tool of liberation work. They eventually want to provide low-cost to free counseling services for QTPOC in their community. In their free time, they enjoy writing poetry, drinking lots of coffee, and creating art.

Lighting candles, burning sage, going to therapy, accessing medication, praying, giving offerings to the ancestors have all been ways that I heal at the intersections of my beautifully complex existence.