Art by Devyn Khaleel Farries

Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, critical race theorist, law professor, and civil rights activist, coined the term intersectionality to describe how different power structures interact in the lives of traditionally oppressed people, specifically Black women. The concept of intersectionality has gained notoriety in the past few years, most recently its absence being a major criticism of White Feminism™ in the 2017 Women’s March.

In the past year, I’ve had the privilege of being added to several private intersectional feminist Facebook groups for women, gender non-conforming, and non-binary people of color. These spaces were created as platforms for us to speak on our personal experiences and to share resources — related to identity or otherwise. These groups are essentially virtual support groups, and have taught me a lot of about what it means to really practice intersectionality.

There is power in storytelling.

In spaces where women and trans persons speak for and about themselves, the discrepancy between our lived experience and how our experiences are represented in media and popular culture become glaringly apparent.

Sharing virtual space with women from a range of backgrounds and who claim many intersecting identities makes it abundantly clear that there is no monolithic “woman” or femme identity, despite what TV, magazines, and movies might tell us. The range of concerns among group members is vast; topics vary from sex practices to cultural appropriation to mental health and wellness.

There is no singular “woman” experience. When we speak, we do so not just as women, but as queer women and trans women and femme women and masc women and cis women and mothers and businesswomen and sexworkers, and the list goes on. Bearing witness to people’s stories about their experiences in the world has deepened my understanding of how oppressive social phenomena – patriarchy, racism, transphobia, sexism, anti-womanism, etc. – interact and manifest in people’s lives.

Visibility is important for each other.

At least once a week, someone starts a selfie thread. One person posts a selfie, and one by one, dozens to hundreds of people respond with photos of themselves. In seeing each other, we are each other’s mirrors – we’re able to celebrate each other, appreciate each other, and affirm each other.

The comments are often gratuitous; members enthusiastically accept the role of being each other’s hype team. Seeing other people celebrate themselves as they are has given me permission to release shame and develop self-esteem about being who I am. Communal visibility allows me to be less self-conscious about things like stretch marks, body hair, and belly rolls, because I see how celebrated these things are on other people.

Seeing each other not only provides evidence of reality, it serves as evidence of possibility. As Marian Wright Edelman said, "You can't be what you can't see.”

Accountability matters.

Intersectionality, at heart, is a social perspective that considers how our many identities contribute to our lived experiences. Our lived experiences inform not only who we are, but what we know. By having a strict accountability culture, these groups encourage members to take responsibility for themselves by admitting ignorance, when appropriate, and doing the work to transform that ignorance into knowledge.

In several groups, there is a strict no deleting policy for comments and posts. Members are expected to take ownership over their problematic opinions, statements, and behaviors as opportunities for them and others to learn.

Accountability is a necessary principle in progressive, safe space; it reflects the individual’s sincere commitment to do less harm.

Culture is created.

Everyone in these groups is expected to adhere to the guidelines set forth by the administrators (for example, to include content and trigger warnings for sensitive material) and to respect the rights and concerns of each member.

Intersectional groups have a zero tolerance policy for oppression, meaning comments and attitudes that demean, demoralize, criminalize, shame, and or misrepresent people are strictly prohibited. Interactions are guided by a shared responsibility to support the growth and wellbeing of members, and group guidelines are used to establish norms for conduct and to ensure that the spaces are safe for everyone participating.

Shared responsibility is a foundational characteristic of community. We, the collective, by deciding to be a part of this communal space, agree to protect and support everyone within it as a condition of our membership.

Joy is resistance.

In these groups, memes, gifs, and humorous videos are widely circulated as comedic relief. Humor provides necessary levity in the midst of burdensome circumstance. The use of humor in these spaces has shown me how healing it is to make room for joy in the midst of suffering.

Members will often solicit funny memes after a bad day and post them in response to current social events. Humor not only becomes the language with which we point out the undeniable absurdity of realities created by white supremacy, patriarchy, homophobia, transphobia, and the like, it also gives us a necessary respite.

Seeing the members of this group be joyful reminds me that I – despite my own personal challenges and difficulties – can, in fact, live a life that isn’t constantly inundated with stress, violence, and trauma. Joy is why we keep going; it is one of the reasons we choose to survive that which seeks to destroy us.

* * *

Virtual groups have been a source and site of personal transformation – they provide evidence that there is always more than dominant narrative. These spaces allow me to reflect upon my lived experience, to bear witness to the lived experiences of other people, and to widen the lens with which I view the world.

Intersectional spaces are invaluable for creating a truly humanistic view of people whose voices and stories are often marginalized, distorted, or entirely erased. As Crenshaw so brilliantly put it, “It’s up to us to consistently tell those stories, articulate what difference the difference makes.”

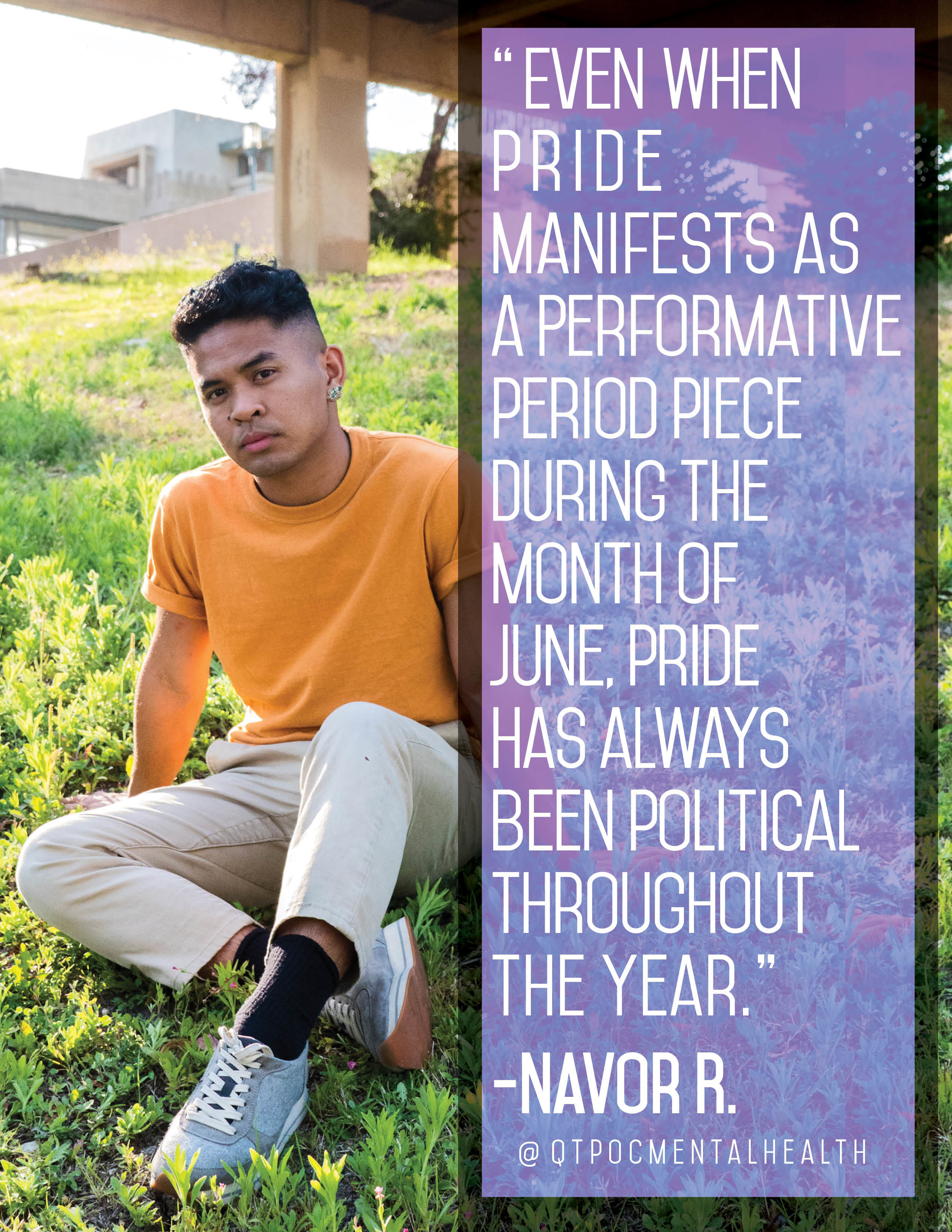

Editor's Note: Did you know we have an intersectional Facebook group for queer & trans people of color? If you're looking to connect with others and gain support around your healing process, join QTPoC Healing Space. You can also follow us on Facebook at Rest for Resistance and QTPoC Mental Health.

We need community support to continue publishing!

Articles and artwork like these are only possible through your contributions. Please donate today to sustain the wellbeing of artists, writers, healers, and LGBTQ2IA+ people of color.

You can also support our team by picking up

a Rest for Resistance print zine.

Image description:

A person is sitting in a dark room looking at a computer. Most of the image is dark blue, and the light from the monitor is reflecting off the person. The screen reads "INTERSECTIONALITY," and there are lines around the monitor and the person's face to depict insight gained from interacting with others online.

About Jamila Reddy:

Jamila Reddy is a writer and creative producer. Born and raised in North Carolina, she is thankful for her freedom and likes to say hello to strangers. As a queer Black femme Buddhist, the intention of Jamila’s work is to deepen a collective understanding of the complexities of the human experience. She believes that joy and pleasure are acts of resistance. She wants to throw your next party. She wants to make you brave. You can find Jamila all over the Internet via her blog, Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter.