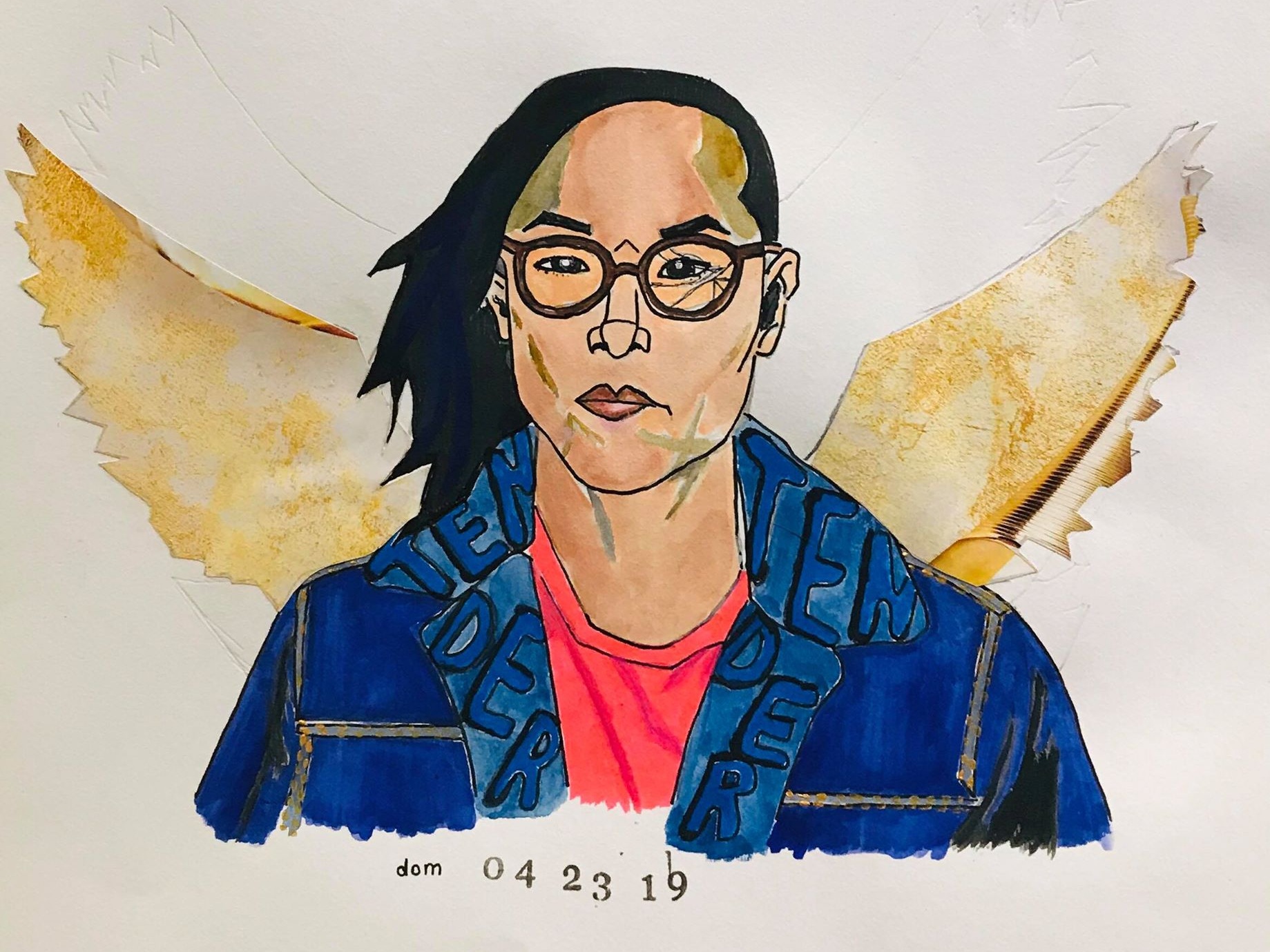

Art by ACACIA

CN: sexual violence

“When you have sex with a man, he takes something from you.”

I nearly choked when my mother said this, her own version of the “sex talk”. I was a few weeks away from starting my first year of college and I suppose my mother was staring to feel the anxiety of not being able to monitor me anymore. Besides, to her, college was probably a haven for debauchery – sex, drugs and rock & roll, I was also a baby feminist at the time and I remember being so angry at her words. What a patriarchal thought, that I lose something just because a penis goes inside me. By then though, I’d learned enough to know not to argue with my mother. Neither of us was going to change the other’s mind so what was the point? I swallowed my disagreement, nodded, and reassured her that I wasn’t planning on having sex with anyone anyway. I fumed privately for hours later. Take something from me, my foot! What a ludicrous idea.

Now, five years later, I am almost amused at how much I agree.

The first time I tried having consensual sex with a cis man, it was a very careful event. I chose him carefully – a friend I knew well enough to trust but not one so close it might be awkward if things ended weirdly. Plus, he was a queer black man. There are no cis men I love more than queer black men. When he came over and sat on my bed and kissed me, the tension in my body was palpable. Even as we went through do’s and don’ts and he confirmed over and over that I wanted to do this, I just got more and more stressed. His hands were too rough, his body too hard, everything was just wrong.

His gentle touch felt violent and I knew, deep in my heart, that this was not a possibility for me.

I anticipate that coming out to my parents will be the most stressful ordeal I ever have to deal with concerning them, but a close second was confessing that I’d been sexually abused. It was not even my choice – a fact that makes me extra careful to avoid being outed. I was in trouble the night I told them. I was a senior in high school and I was in my little black dress, so excited to go to my homecoming dance. Unfortunately, I’d gotten caught in a lie about something or the other and my mom was lecturing me. I’m not quite sure how it got to this but at some point, my mother pulled out the big question: “were you abused?”

I was so new to lying about aspects of my identity back then,

that I just blinked at her.

At some point, my eyes filled with tears and with each blink, a tear fell. She asked again, “were you abused?” It felt like a million years later when I nodded. I will never forget that particular homecoming dance because I kept taking breaks from grinding on my friends to go cry in the bathroom. It was a surreal moment when I told her – while the secret I’d been carrying for almost ten years was finally out, I also felt so naked and exposed without it. After the dance, I had a lengthy talk with my parents. My father, well-meaning but lacking the correct words, asked me if my abuser had “made love to me.” I think I’ve carried this conflation of abuse and love with me since.

Before I became queer/realized my queerness, every time I had a crush on a cis man, my best friend asked if I would have sex with the object of my affection.

My answer was always yes until one day when it was “I don’t know.” How does one go about trusting a cis man when one’s body still bears bruises from the last one? No matter how different they said it would be – abuse and sex – I couldn’t extricate one from the other. The act would not be different, so how could the effect be? Some cis man would try to “make love” to me the exact same way as the last person who touched my body. This was in no way whatsoever, anything I wanted.

I realize now what the first man who touched me took from me.

He took my ability to trust another man with my body. Along with all those other men whose hands found ways to forbidden territories, he took my ability to associate men with anything but plunder and greed and danger and pain. Men who touch me scorch my skin and bruise me.

It is funny to me that my mother’s own words might be the perfect ones to explain my queerness. Often, I wonder if I love women because I’m tired of being hurt by men. In effect, I have the same question many queer survivors have: am I queer because I was abused? Sometimes it upsets me because I don’t really know. Maybe I am. Maybe I’m not. I have found that most of the time, for me, I don’t care. The women I have loved have taught me what it actually is to “make love” and that is enough for me.

I don’t really care how I “got” queer, I’m just happy to be here now.

We need community support to continue publishing!

Articles and artwork like these are only possible through your contributions. Please donate today to sustain the wellbeing of artists, writers, healers, and LGBTQ2IA+ people of color.

You can also support our team by picking up

a Rest for Resistance print zine.

Image Description: Two people sit back-to-back in front of a background of pink flowers. One person has dark skin, short teal hair, a blue button-down shirt, and black slacks. On the left is a person with long voluminous red hair, a septum piercing, a green tank top over a pink bra or binder, and khaki shorts with black boots.

About O.T. Taylor is a freelance writer based in DC. She is interested in exploring the many intersections between blackness, queerness, gender, and sometimes religion. She can usually be found stanning for black women, writing, watching copious amounts of TV, and cooking.

About ACACIA (uh|kay|shah): A Queer Afrolatinx multimedia designer devoted to visually amplifying the voices of Queer, Trans, Nonbinary and GNC peoples.

"My artistic practice is informed heavily by my exploration of what it means to make art with and for people largely unacknowledged on a global scale. Looking through a decolonized mindset lens, I use graphic design, illustration, and photography to generate content that appeals to a wide variety of people. By working with a talented and diverse community of designers, performers, writers, organizers, and thinkers, I am able to create amongst people who instill art with a philosophy of beauty, acceptance, and radical creativity. My goal when creating art is to imbue it with the intention to include and incite the voiceless, to develop their own unique approach of what it means to create art.“